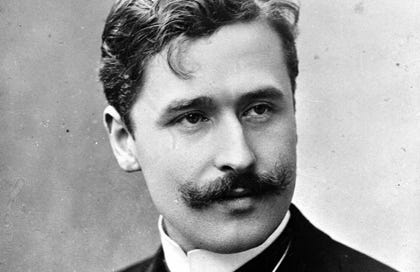

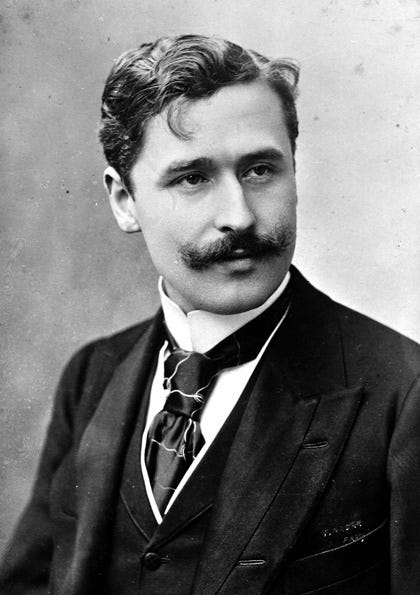

Le Journal de lecture. Georges Feydeau.

Review of Georges Feydeau's play "Chat en poche".

Georges Feydeau

(1862 - 1921)

CHAT EN POCHE

(Lit. “Cat in the pocket” . In english translation “A pig in a poke”)

Final score: 3+ (out of 5)This was my first encounter with the work of Georges Feydeau and the vaudeville genre in general.

The choice of 'Chat en poche' was not based on any particular considerations. To provide a bit of historical context, Feydeau is considered one of the last representatives of vaudeville in the sense of a light theater comedy genre that has developed in France since the late 18th century. 'Chat en poche' appeared in the middle period of Feydeau’s career. Although the first performances of this work failed, the play gained considerable success in the second half of the previous century and has since become part of the repertoire of many French theaters.

In my review, I do not intend to discuss this play in the context of vaudeville as a genre. Instead, I aim to share my opinion on the play as a standalone piece of playwrighting.

First of all, I must admit that, as far as I remember, I have never read a play with such a high number of humoristic elements. The virtuosity with which Feydeau turns each dialogue and subplot into a twist of comic absurdity is truly remarkable. The piece throws you into a whirlpool of concisely expressed misunderstandings and miscommunications, starting with that Pacarel confusing the son of his acquintance for a famous singer. The play truly flies like a skyrocket, fueled by distinctively bold dynamism! During the first two acts, there were several moments where I had to pause just to catch my breath and digest the wildness of Feydeau’s humor. This might also be one of the main reasons why the play initially failed; some aspects of the humor were simply too acrid for the audience of that time. For instance, one of the main characters introduces himself with: “Je me suis enrichi dans la fabrication du sucre par l’exploitation des diabétiques” (I have enriched myself in the manufacture of sugar by the exploitation of diabetics).

Without spoiling the vast range of Feydeau’s jokes, I would like to introduce a couple of the most recurring types of humor.

Firstly, one cannot overlook the large number of puns around the French language. This trait also raises questions about the possibility of translating this play into any other language. One recurring example of perplexity around the words themselves can be found in the scenes with the servant Tiburce.

Pacarel. – (…) (À Tiburce.) Eh ! (…) J’ai demandé que vous m’apportassiez les rince-bouche.

Tiburce. — Voilà ! Je vais vous l’apportasser !

Pacarel. — D’abord on dit apporter… On ne dit pas apportasser.

Tiburce. — Ah ! je pensais faire plaisir à Monsieur… comme Monsieur vient de le dire… Oh ! les maîtres !…

___

(Pacarel. – (To Tiburce) I asked that you apportassiez (bring) me the mouthwash!

Tiburce. - There you go! I'll apportasser (bring) it to you!

Pacarel. — First we say apporter... We don't say apportasser.

Tiburce. - Ah! I intended to please the Monsieur ... as the Monsieur had just said ... Oh! the masters!…)

The salt of this little interrogation is all about French grammar. The “apporter” is the French infinitive for “bring.” And according to the French grammar, a verb takes a conjunctive form after certain use of the word “que” (that) which is the case in the Pacarels remark:

“J’ai demandé que vous m’apportassiez les rince-bouche”.

Hearing this, however, Tiburce deduced a made up infinitive “apportasser” which simply does not exist. So instead of grammatically correct “Je vais vous l’apporter” he utters “Je vais vous l’apportasser”.

In another scene, Tiburce mistakes 'laudanum' for 'l’eau danum,' a confusion that only makes sense in French since the first syllable of 'laudanum' sounds like the French word for water, 'l’eau.' Following this misunderstanding, Tiburce confidently mixes up the masculine and feminine articles.

Tiburce. — (…) Je crois, entre nous, que si l’on dort si longtemps aujourd’hui, c’est parce que, hier, la cuisinière, n’ayant plus de caramel, pour colorer le bouillon, y a mis de laudanum.

Landernau. — Du laudanum ! Vous êtes fou !

Tiburce. — Oui, monsieur. (Appuyant sur chaque syllabe.) De l’eau danum.

Landernau. — Allons donc ! vous ne savez pas ce que vous racontez aujourd’hui… et puis, d’abord, on dit : du laudanum.

Tiburce. — Comment "du" ? eau est du féminin, Monsieur ! Monsieur ne dit pas du l’eau-de-vie… passez-moi du l’eau… On dit de l’eau-de-vie, de l’eau danum ; la grammaire est la même pour les domestiques comme pour les maîtres.

Landernau. — Quel idiot !

___

Tiburce. - (…) I believe, between us, that the reason we are sleeping so long today is because yesterday, the cook, no longer having caramel, to color the broth, put de laudanum in it.

Landernau. - Du Laudanum! You're crazy!

Tiburce. - Yes, sir. (Pressing on each syllable.) L’eau Danum.

Landernau. - Come on, what you're talking about today... and then, first of all, we say: du laudanum.

Tiburce. - Why "de"? It's feminine, Sir! Monsieur does not say du l’eau-de-vie ... pass me du l’eau ... They say de l’eau-de-vie, de l’eau danum; the grammar is the same for servants as for masters.

Landernau. - What an idiot!

Another type of humor that stays to Feydeau’s service is the outright absurdity of remarks caused by the exaggeration of conventional comments, as seen in the following scene:

Amandine. — Ne rougissez pas, jeune homme…

Dufausset. — Je ne rougis pas !…

Amandine. — Ainsi, quand je vais dans la colonne Vendôme… Ne blanchissez pas, jeune homme !

Dufausset. — Mais je ne blanchis pas !

Amandine. — Souvent on se croise, on se rencontre… une fois, entr’autres… il descendait, je montais… je me suis effacée…

Dufausset. — Allons donc ! Comment avez-vous fait ?

Amandine. — Il m’a frôlée… Ne verdissez pas, jeune homme !

Dufausset. — Mais je ne verdis pas !… Elle voudrait me faire passer par toutes les couleurs !…

___

Amandine. — Don't blush, young man…

Dufausset. — I'm not blushing!…

Amandine. - So, when I go to the Vendôme column... Don't get pale, young man

Dufausset. - But I'm not paling!

Amandine. — Often we meet, we meet ... once, between others ... he was coming down, I was going up ... I erased myself…

Dufausset. - Come on, then! How did you do it?

Amandine. - He brushed me off... Don't turn green, young man!

Dufausset. - But I'm not turning green!... She would like to make me go through all the colors!…

And thirdly I would like to point out scenes where Feydeau went as far as adroitly mingling the both types of humor, tense them with the cords of highest intensity and spice them with an uncannily lowness of a character’s intelligence as it is the case in the scene where Pacarel introduces Lanoix, his son-in-law to Dufausset.

Lanoix. — Ah ! Cher beau-père…

Pacarel, présentant. — Monsieur Lanoix de Vaux, mon futur gendre… Monsieur Dufausset, un Duprez de l’avenir…

Lanoix. — Ah !… Monsieur est peintre ?…

Dufausset. — Moi !

Pacarel. Mais non… monsieur s’occupe de chant.

Lanoix. — Paysagiste alors !…

Pacarel. — Mais non… (À Dufausset.) Il est bouché mon gendre…

Dufausset. — Boucher ?… Fichu métier !…

Lanoix. — Je vais vous dire, c’est que moi je me destine à la peinture comme mon père…

Dufausset. — Ah ! votre père se destine…

Lanoix. — Non, il est mort… il était peintre en animaux.

Pacarel. — Il a même fait le portrait de mon gendre ! Superbe !

___

Lanoix. - Ah! Dear father-in-law…

Pacarel, introducing. - Mr. Lanoix de Vaux, my future son-in-law... Mr. Dufausset, a Duprez* of the future… (*Gilbert-Louis Duprez was a well-known tenor singer of that time)

Lanoix. - Ah!... Is the gentleman a painter?…

Dufausset. - Me!!

Pacarel. But no... the gentleman is into singing.

Lanoix. - Landscape designer then!…

Pacarel. - But no... (To Dufausset.) He is “bouché” (“dumb”) my son-in-law…

Dufausset. - boucher? (“Butcher”)... Damn job he has!…

Lanoix. — You know, the thing is that I am destined for painting like my father…

Dufausset. - Ah! your father is destined…

Lanoix. - No, he's dead... he was an animal painter.

Pacarel. — He even made a portrait of my son-in-law! Superb!

This list is by no means exhaustive; it is just a drop in the broad sea of humor, puns, ridiculous actions, and mockery of social norms that fill 'Chat en poche' as water does the human body.

All this contributes to the high dynamism of the entire work. Even the few monologues that appear in between are so thoughtfully executed and placed that they do not hinder the dynamism in the least. On the contrary, they bring even more stimuli and intrigue to the plot development.

Speaking of the plot, which also dazzles with a wide range of witty twists, I agree with the French biographer Henry Gidel, author of the introduction and notes to the play in older editions, that we should not judge the vaudeville plots too harshly. The maneuvering room for plot-building in this genre is quite limited. Instead, we should focus on the technique and quality of the story development. In the case of 'Chat en poche,' Feydeau did a good job, but unfortunately, only until the third act, which is the work’s considerably weak spot. The play did not reach a satisfying ending, leaving bitter sediment.

As I see it, Georges Feydeau decided to take the easy way out by simply putting ends to all the plotlines. The way he executed it appears too mundane. After being caught up in such a whirlpool of events, I, as a reader, was expecting a dynamic end with an additional confrontation. But what Feydeau offered me was just an unfairly pathetic ending to such a play and that considerably lowers my final score.